| |

Nephie Christodoulides

Sylvia Plath’s “The Magic Mirror”: A Jungian Alchemical Reading*

In this paper I propose a new reading of Sylvia Plath’s Honor Thesis “The Magic Mirror,” a reading which, like the idol in a magic mirror demonstrating a disturbance from the reflected item [1], will depart from prevalent psychoanalytical critical approaches in order to exhibit a latent Jungian alchemical veiled perspective that revolves mostly around the seminal alchemical principle of hieros gamos. This reading is by no means exhaustive, but should be seen as part of a project in its preliminary stages to unveil alchemical allusions, as the very manifestation of Sylvia Plath’s early interest in the occult before Ted Hughes’ initiation. A Jungian reading of Sylvia Plath’s early work will be crucial to perceiving the overall preoccupation of both Sylvia Plath and Hughes with alchemy.

Sylvia Plath’s interest in the occult is very often seen as triggered by Hughes’ mystical initiation. Alvarez observes that magic and occultism “worked fine for him, and even made sense” but proved fatal for Sylvia Plath and by “the end, the pseudo black magic which Ted used cannily to get through to the sources of his inspiration had taken her over.” Alvarez sees Hughes’ training as originally serving a poetic purpose, but he blames him for not realizing the consequences of such acts (“How Black Magic Killed Sylvia Plath”). For Hughes, Sylvia Plath resorted to occultism in an effort to break with traditional culture and religion, regressing, like other contemporary writers, to the “pre-Christian spirit” (Timothy Materer 125); he also sees this preoccupation as a stage in her poetic development as it helped to liberate her creative energies (Timothy Materer 126). Timothy Materer in his Modernist Alchemy, in a close reading of Sylvia Plath’s verse dialogue “Dialogue Over a Ouija Board,” sees her immersion in the ouija board as closely connected “with the dominance of her father’s authority” (Timothy Materer 131). Judith Kroll in her seminal Chapters in a Mythology, in her discussion of the central symbol of the moon in Sylvia Plath’s poetry, has very wisely observed that Sylvia Plath adopted Jung’s “archetypes of the collective unconscious” (Judith Kroll 77). She also mentions that Sylvia Plath was reading Jung’s insights on “the development of personality,” which involves allowing “the inner voice” to “lead [one] towards wholeness” and considered marriage as “a psychological relationship.” Of particular interest for Judith Kroll is the fact that Sylvia Plath had transcribed certain excerpts from Jung’s “Marriage as a Psychological Relationship” which involves a relationship between anima (“the eternal image of woman”) with animus (“the image of man projected by the unconscious of women”) (Judith Kroll 77). Of course such preoccupation is manifested much later in Sylvia Plath’s life during the dissolution of her marriage which proved to be an ill compromise of anima and animus. Interestingly enough, Judith Kroll also observes Sylvia Plath’s preoccupation with the notion of “the sacred marriage,” but she sees this as emanating from her reading of James Frazer’s The Golden Bough and associates it with her relationship with her dead father (Judith Kroll 86-87).

While Paul Alexander sees Sylvia Plath’s occultism “as a stage in her poetic development and a source of her mature symbolism,” Anne Stevenson in her biography of Sylvia Plath sees this “as a symptom of [her] psychological instability” (qtd. in Timothy Materer, 126). Sylvia Plath’s preoccupation with the occult is of course discussed by other critics who usually cite poems such as “Snake Charmer,” “Witch Burning,” or the story “Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams,” which she composed after meeting Hughes. Less reference is made to “Sonnet to Satan,” “Moonsong at Morning,” “Metamorphoses of the Moon,” “On Looking into the Eyes of a Demon Lover” or “Danse Macabre,” written before 1956. It is my conviction that her interest in the occult predated her meeting with Hughes as I will prove and that their union merely intensified it.

Interestingly enough, in a 1952 Journal entry, Sylvia Plath is reflecting upon sexuality, sensuality and subjectivity and she seems divided between the two polarities inherent in a sexual relationship: “devouring “and “subordination” (Timothy Materer 105). She rejects either but finds a compromise in polarization: “a balance of two integrities, changing, electrically, one with the other, yet with centers of coolness like stars …. A balanced tension; adaptable [sic] to circumstances, in which there is an elasticity of pull, tension, yet firm unity” (Ibid.). As she admits, such thoughts derive from her reading of D.H. Lawrence. In fact it is from his Women in Love that she is quoting and quite surprisingly, the excerpt she has in mind is the conversation between Gudrun and Gerald which focuses on marriage. The term used is “conjunction,” the English translation of the terms coniunctio, which as we will see, is a seminal term in alchemy.

- see note [2] - see note [2]

Further, that she was familiar with the occult, can be inferred from a small, Hermetic caduceus that she carved when she was fifteen, which bears Hermetic symbols, now in the possession of Professor Richard Larschan.[3] It may also be inferred that she was familiar with the Tarot as Ruth Barnhouse used it, among other unorthodox methods, to cure her patients. Further, Stevenson talks about the pack of tarot cards that Sylvia Plath had brought from America to England and which she used to teach Ted and Olwyn Hughes “the game of tarok, learned from her grandmother” (Anne Stevenson, Bitter Fame, 178). Finally, interestingly enough, Aurelia Plath’s MA thesis at Boston University was entitled “The Paracelsus of History and Literature” (1930). There is no evidence whether Sylvia Plath had read the thesis and recycled parts of into in her work, but bearing in mind “the psychic osmosis” (Letters Home, 32) that existed between mother and daughter and which was extended into a “reading” osmosis with mother reading the daughter’s books and daughter the mother’s, as well as the fact that Sylvia Plath had read Otto Plath’s Bumble Bees and Their Ways (ghost written by Aurelia) and recycled parts of it in her “bee” poems, the odds that she must have read the thesis are many.[4] Very proudly Aurelia states in her introductory notes to Letters Home: “Sylvia read almost all the books I collected while I was in college, used them as her own, underlining passages that held particular significance for her” (Letters Home, 32).

It is my conviction that one of the most significant examples of her alchemical interests, albeit veiled, is her Honor thesis which is seen by many scholars as her lay self-analysis to cope with her schizophrenia. Plath wrote the thesis in 1954-55 after her 1953 suicide attempt. George Gibian, her advisor, claims that her interest in the double was personal, reflecting “her continual intellectual awareness of her own schizophrenic nature” (Ibid.). In contrast to her other papers submitted for course requirements, the thesis is not noted for her original critical perception but for the fluent reiteration of previous scholarship on the issue of the double and the way she applies it to Dostoevsky’s The Double and The Brothers Karamazov. In a letter to her mother (October 15, 1954) she expresses her concern that the thesis will lack originality:

The rough draft of my first chapter is due in a week from this Friday, and I am

wondering if I can say anything original or potential in it, as I feel always that

I have not enough incisive thinking ability – the best thing is that the topic

itself intrigues me and that no matter how I work on it, I shall never tire of it.

It is specific, detailed, and with a wealth of material; but of course, I don’t

know yet what precise angle I’ll handle it from (Aurelia Plath,Letters Home, 145).

In her theoretical coverage she seemed to be oscillating between Otto Rank’s modern and Sir James Frazer’s primitive notions. In between, Freud made his appearance, reiterating Rank’s “Doppelgänger” (Magic Mirror, 17-18). Concerning other theoretical sources in a letter to her mother she did mention Jung (Letters Home, 146), whom however, she did not cite anywhere in the thesis, although she made reference to the notion of the shadow and its implications, an idea Jung promoted mostly in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, but also by Frazer, especially his “excellent chapter on ‘the soul as shadow and reflection’” (Ibid., 145).

In her discussion, Plath reiterated the familiar association of the appearance of the Double with “man’s eternal desire to solve the enigma of his own identity” (Magic Mirror, 1) and the feelings of curiosity and fear such confrontation entails. She observed that it was the psychic state of the individual that determined the nature of each split character, and careful study of these different manifestations would enlighten the “essential discord from which the division originally grew” (Ibid., 4). Although the approach seems to be purely psychoanalytic, a closer look at the notion of the mirror, which Plath very boldly used in the title she gave to her thesis, will reveal its affinity with the principle of the alchemical wedding and the concept of harmony this entails.

Sylvia Plath’s fascination with mirrors starts at a young age when she is introduced to Carroll Lewis’ Alice in Wonderland, a book she will cherish until the end of her life. Much like Alice, she is preoccupied with what lies beyond the mirror, since for her the mirror symbolizes not only the intellect’s capacity to “reflect with indifferent precision” only that layer of reality which the senses can register, but also what lies beyond. She writes in her childhood memoir “Ocean 1212-W” about the Atlantic on its southeastern part around the Point Shirley peninsula, where her grandparents’ beach house was: “I often wonder what would have happened if I had managed to pierce that looking glass” (Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams, 117). Behind the watery mirror, she could become a sea-girl torn by the question, “[w]ould my infant gills have taken over [or] the salt in my blood?” (Ibid.). Surprisingly enough, salt is one of the three alchemical principals, the ingredients of the alchemical opus which will give out the philosopher’s stone, the others being sulfur and mercury. Salt is analogous to the human body, while sulfur is the spirit of life and mercury the symbol of the soul. The question Sylvia Plath raises expresses her fears about an imminent discord: what will happen if one predominates? Unlike the alchemical opus which must be governed by absolute harmony to be successful with the merging of the three contraries, the journey behind the sea mirror is likely to entail a disturbance that the adult Plath perceives from a nachtraglich perspective since she has already seen it governing her life.

What interests us at this point is the mirror as the very concept of the disturbed double and the way this could be associated with the alchemical double, an idea embodied in the notion of “Mysterium Coniunctionis.” The alchemical sacred marriage is often referred to as “The Hieros Gamos” or union of opposites, as mentioned before, sulfur, mercury and salt. The product of this marriage is Hermaphrodite or “Divine Child,” who is a fusion of both the male (positive) Sol/sulfur, and female (negative) Luna/mercury, polarities. (Carl Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 231-32).

Sylvia Plath uses the term “Hermaphrodite,” in her chapter “The Psychic Hermaphrodite,” ostensibly referring to the duality in Golyadkin’s nature, the discrepancy between Golyadkin senior and Golyadkin junior, as Plath calls the two polarities. Rather than representing the “synthesis of opposites,” like Hermaphrodite, the two polarities are in constant conflict: “Golyadkin junior seems to be the exact opposite of his original in personality traits. Where Golyadkin senior considers himself honest, awkward, and meek, his Double appears hypocritical, nimble and aggressive” (Magic Mirror, 7-8).

The reference to “Hermaphrodite” as the Jekyll and Hyde personality of Golyadkin, may not be an apt or accurate term for Sylvia Plath to have chosen, since in the face of Hermaphrodite the union is balanced, whereas no balance exists between Golyadkin and his alter ego. Golyadkin junior is in perennial conflict with Golyadkin senior and the lack of harmony results in insanity. As Plath states, Golyadkin’s “inability to acknowledge his inner conflict […] result[s] in severe schizophrenia. For Carl Jung the alchemical opus and its successful culmination in cauda pavonis, the white light, is analogous to the process of individuation, a point at which the person achieves his/her wholeness and discovers his/her true nature.[5] In a similar way, for Sylvia Plath, the conflict is a fundamental search for identity in which the two selves must necessarily co-exist in a balanced form in order for their host to survive; as she puts it, it is a “reconciliation of [man’s] various images [which] involves a constant courageous acceptance of the eternal paradoxes within the universe and within ourselves.” As a foil to Hermaphrodite, Golyadkin is destroyed by insanity.

The chapter in which Plath discusses in detail Ivan Karamazov’s religious conflict is titled “The Crucible of Doubt.” The title is indicative of the double entendre of the term “crucible.” First, it may simply be considered a figurative expression of Ivan’s oscillation between the “acceptance of the regenerating power of the law of Christ” and atheism (Magic Mirror, 29-30) and the fact that from “the soil of psychic vacillation springs the form of Ivan’s Double” as Smerdyakov, his father’s bastard son and the Devil (Ibid., 34). Secondly, in alchemical jargon “crucible” is the vessel, the Vas Hermetis where the alchemical opus takes place, thus constituting an integral part of the Jungian individuation process. Since this chapter focuses on Ivan’s religious doubt, if crucible stands for the alchemical Krater, a kind of matrix or uterus from which the filius philosophorum, the miraculous stone is to be born, out of the reconciliation of the opposing forces, then it is contrasted with Ivan’s conflict between belief and unbelief which is not resolved and leads to his insanity and Smerdyakov’s suicide: “the doom of madness, where conflicts in the psyche are projected in the for of hallucinations” (Magic Mirror, 44).

Why did Plath resort to Jung and why did she opt for a mystic, magic Jungian alchemical tint? Carl Jung talks about “the projection of pairs of opposites” (Carl Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 282) in his mystical marriage, as the alchemist’s alchemical marriage, becomes the final goal of the individuation process. For him this “inner psychic development [grew] from a state of conflict towards one of inner freedom and unity, which is symbolized in the idea of the mystic marriage or union.” The harmony of opposites can also be the harmony in the actual marriage between man and woman, or the harmony between the masculine and feminine aspect within the individual psyche, what Plath would call “a balanced tension” in a 1952 Journal entry (Journals, 105). The harmony proposed by Jung is what she actually covets and throughout the thesis she stresses its importance within the psychical duality. There are more than 20 references in the whole thesis, on the one hand confirming the existence of the double, citations such as: “recognition of contradictions in man’s character,” (2); “the duality of man” (4); “every person is born with a double.” On the other hand, she very often repeats the need for reconciliation which brings harmony: Golyadkin is led to insanity because the opposing parts “are never joined” (10), and “he refuses to accept them as an integral part of his personality” (15).

In his Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy, Carl Jung proves that his study of the problem of philosophical alchemy and the synthesis of opposites in the human psyche provides a way of viewing neurotic and psychotic processes. This constitutes an additional healing process for Sylvia Plath, as it confirms her very realizations and materializes her desire to put them down on paper. The appeal to Jung to confirm her belief in the existence of the double and the importance of the reconciliation of the polarities offers both attraction and repulsion: attraction because his individuation process, the psychic evolution within the life span of an individual existence reverberates her own subjectivity trajectory; repulsion, because he may be seen as another paternal figure. As is well known, Jung was pro-German in his political sympathies and acted as president of the Nazi-controlled International General Medical Society and editor of the official organ of the society. Much like Sylvia Plath’s German father Otto he both attracted and repelled. The German father is hated and his German language is “obscene” and intimidating. But “Every woman adores a fascist,” and she cannot ignore his existence for he is “somewhere in [her], interwoven in the cellular system of [her] long body” (Journals, 64). In the same way, she seems to be longing for Jung’s symbolic language [much like her father’s Botany, Zoology and Science jargon – (Journals, 64)] because it gives her the hope that she wants, the harmony to come out of conflicting dual elements, but because it is paternal and could be oppressive, she opts to veil it.

Jung observes that the antithetical nature is an almost universal idea. He mentions the Chinese opposites of yang and yin, “odd and even numbers, heaven and earth,” and proceeds to discuss the role of hybrids, citing examples such as Nicomachus’ notion of the Deity as the odd and even number, therefore male-female, of Hermes Trismegistus: the nous (mind) which is hermaphroditic, and Pneuma which is malefemale (Carl Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 330). Interestingly enough, in a 1956 Journal entry, Plath talks about the desirable balance of opposites in the self but also in men-women relationships. She covets a “balanced tension, adaptible [sic] to circumstances […] stars polarized” (Journals, 105). She is well aware that absolute fusion is impossible (Ibid.) and throughout her life she strives for “reconciliation of opposites.” In vain. In her marriage, she saw herself as an “earth goddess” and Hughes as the sun, “the black complement power: yang to yin” (Journals, 287), but this marriage of opposites failed since it did not reach balance. And her suicide, as Kristeva saw it, becomes the very manifestation of her failure to resist the call of the mother and balance the opposing realms of the paternal symbolic and the maternal semiotic (Toril Moi, ed.The Kristeva Reader, 157).

*Nephie Christodoulides; Sylvia Plath’s “The Magic Mirror”: A Jungian Alchemical Reading, Plath Profiles: An interdisciplinary journal for Sylvia Plath studies , Vol 1 (Summer 2008), Indiana University.

Notes

1 Plath is in this case borrowing Dostoevsky’s technique, who as she sees it, “often uses dreams to reveal in the manifest content of dream-form the latent fears and desires which the character cannot consciously acknowledge when awake” (Maggic Mirror, 22).

2 photo The caduceus of Mercury Plath engraved at the bottom is one of the most significant hermetic symbols. It comprises a short rod, entwined by two snakes and topped by a pair of wings. One can also observe the snake motif which for alchemists embodied “the cosmic spirit which brings everything to life,” as stated in Donum Dei, 1735.

3 Personal conversation, October 25, 2007.

4 Paracelsus is considered the greatest alchemist of his time. In his paper “Paracelsus as a Spiritual Phenomenon,” Jung further expands Paracelsus’ notion of the existence of the two sources of Gnosis, Lumen Dei (manifested in the mystery of Incarnation) and Lumen Naturae (to be captured through the alchemical work) [Jung, Carl; Alchemical Studies, 112-13].

5 As Jung states in The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious: “I use the term ‘individuation’ to denote the process by which a person becomes a psychological ‘individual,’ that is, a separate, indivisible unity or ‘whole’” (275).

Works Cited

- Paul Alexander; Rough Magic: A Biography of Sylvia Plath. London: Penguin Books, 1991.

- Al Alvarez; How Black Magic Killed Sylvia Plath. Guardian Unlimited, 15 Sept.1999. 22 Feb. 2007.

- Carl Jung; Alchemical Studies. R.F.C. Hull, trans. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989.

- Carl Jung; Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. R.F.C. Hull, trans. Princeton: Princeton U, 1983.

- Carl Jung; Psychology and Alchemy. R.F.C. Hull, trans. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Carl Jung; The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. R.F.C. Hull, trans. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989.

- Judith Kroll; Chapters in a Mythology: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing, 2007.

- David Herbert Lawrence; Women in Love. Project Gutenberg. 10 May 2008.

- Timothy Materer; Modernist Alchemy: Poetry and the Occult. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1955.

- Toril Moi (editor); The Kristeva Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.

- Sylvia Plath; Collected Poems. London: Faber & Faber, 1989.

- Sylvia Plath; Magic Mirror. Unpublished Honor Thesis, Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, abbreviated as MM.

- Sylvia Plath; Journals. Karen Kukil, ed. London: Faber & Faber, 2000.

- Sylvia Plath; Letters Home. Aurelia Plath, ed. London: Faber & Faber, 1990.

- Sylvia Plath; “Ocean 1212-W.” Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams. London: Faber & Faber, 1990. 117 - 124.

- Anne Stevenson; Bitter Fame: A Life of Sylvia Plath. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

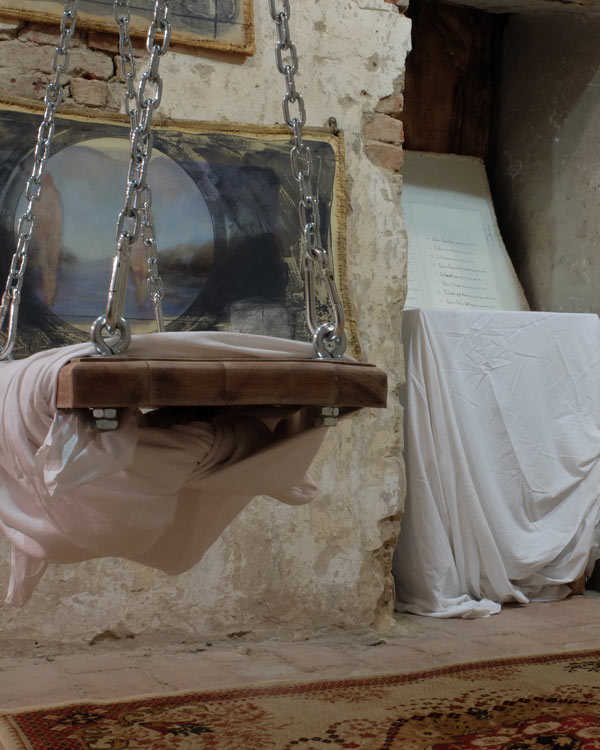

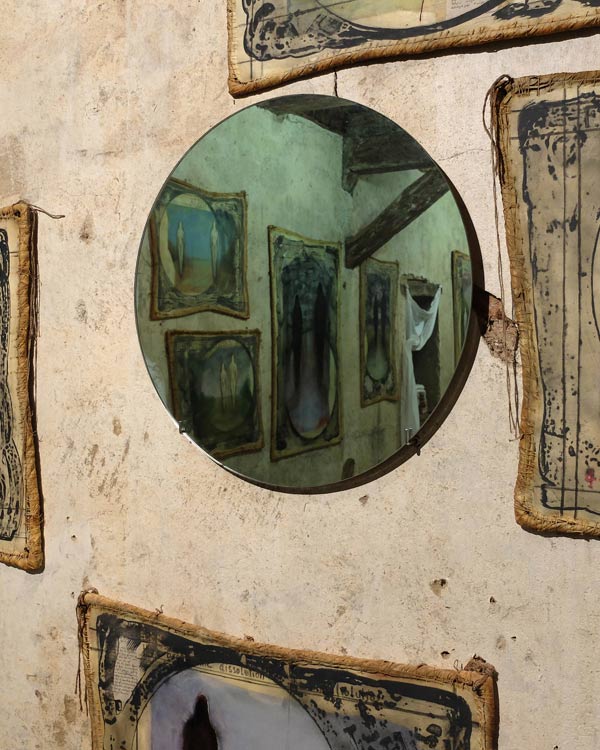

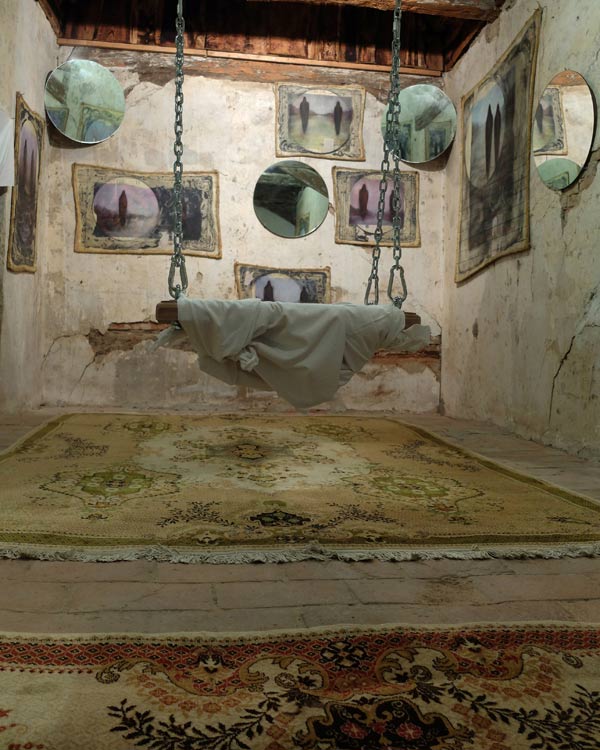

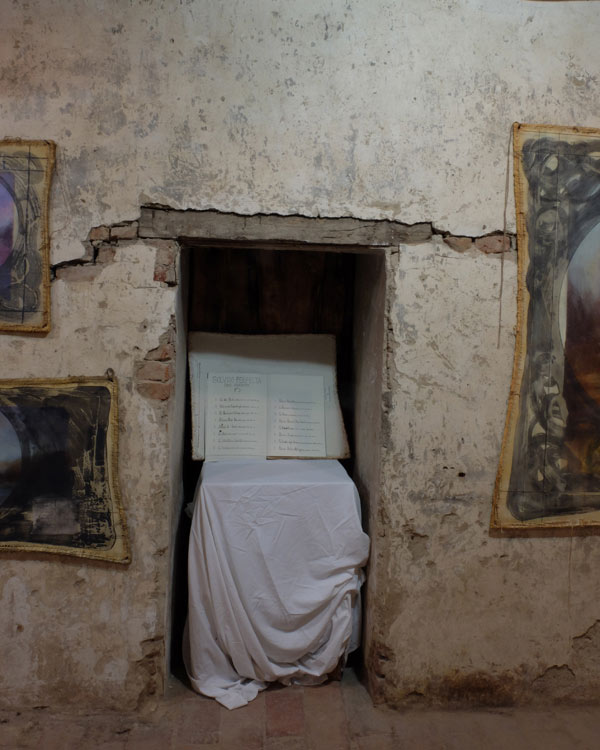

The Magic Mirror - Solutio Perfecta

|

|

...

...  ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

... ...

...